The Centre, The Margin, and The Future of Indian Cinema

PVR-INOX Vs Connplex Cinemas | ZN Research Lab #32

In my previous blog, I attempted to compare and contrast the story of a new entrant with an incumbent. A few comments and DMs suggested that the comparison is unfair. One has been in the industry for 3 decades, and the other has spent barely a few years. I politely disagree with all those comments. I believe that “compare and contrast” is a compelling mental model. You are not trying to predict a winner or a loser. Neither drawing a neat black-and-white divide. You are going one level deeper.

At its core, “compare and contrast” is a way of thinking that helps you make better decisions by looking at similarities and differences side by side. Most people compare only one thing at a time. But when you place two things next to each other, the truth becomes clearer, the patterns become visible, and the blind spots disappear.

Think of it as turning on two lights instead of one. The shadows become smaller. Because your brain understands things relatively. You rarely know if something is good or bad on its own. You know it only when you place it next to something else. That’s how relative valuation was born as well. No doubt, Discounted Cash Flow [DCF] is the holy grail of valuation. But can you do it successfully for businesses you invest in?

Today’s story is no different, but with one twist: my inherent bias. In the previous blog, my liking and association with the incumbent significantly influenced my thoughts. In this case, my dislike of a business model that I believe is ripe for disruption will influence my perspective on this sector.

Eighteen months ago, in May 2024, I wrote this piece, asking myself a simple question:

Is PVR/Inox really a monopoly business?

For me, the resounding answer was a big NO.

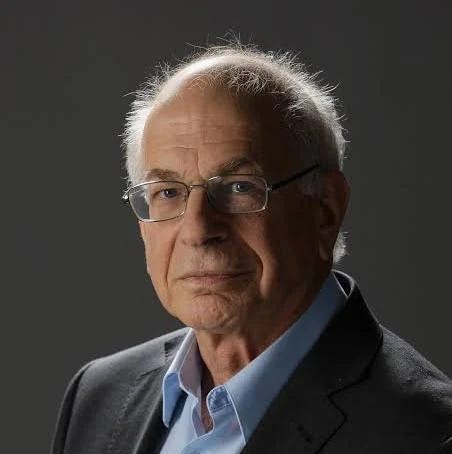

I may be biased. I may be affected by WYSIATI. Don’t you know what WYSIATI is? Then you have not read much about this man.

For the uninitiated, he is Daniel Kahneman: one of the top psychologists to have walked on earth. Daniel Kahneman’s idea of What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI) explains something very human: when we have a set of facts in front of us, our mind quickly constructs a complete story out of them, even if the data is incomplete, selective, or missing important counterpoints. The brain dislikes gaps. So it fills them. And once it fills them, the story feels true. System 1 creates the narrative. System 2 simply nods along. Hence, I have no shame in admitting that I am probably affected by WYSIATI. So be it.

While you may read my bearish take on PVR Inox here for more context, the crux of my thesis was this:

An industry is ripe for disruption when a monopolist is finding it difficult to dominate the market as much as it thinks it should. And I am not talking about theatres being disrupted by the OTT market. There are other ways to bring more people to the theatres. PVR Inox, at the centre stage, has not cracked that yet. And maybe, someone else on the margin will.

And the market is always a leading indicator. The stock of PVR Inox has grossly underperformed the broader market since the merger of Inox and PVR.

Source: Google Finance

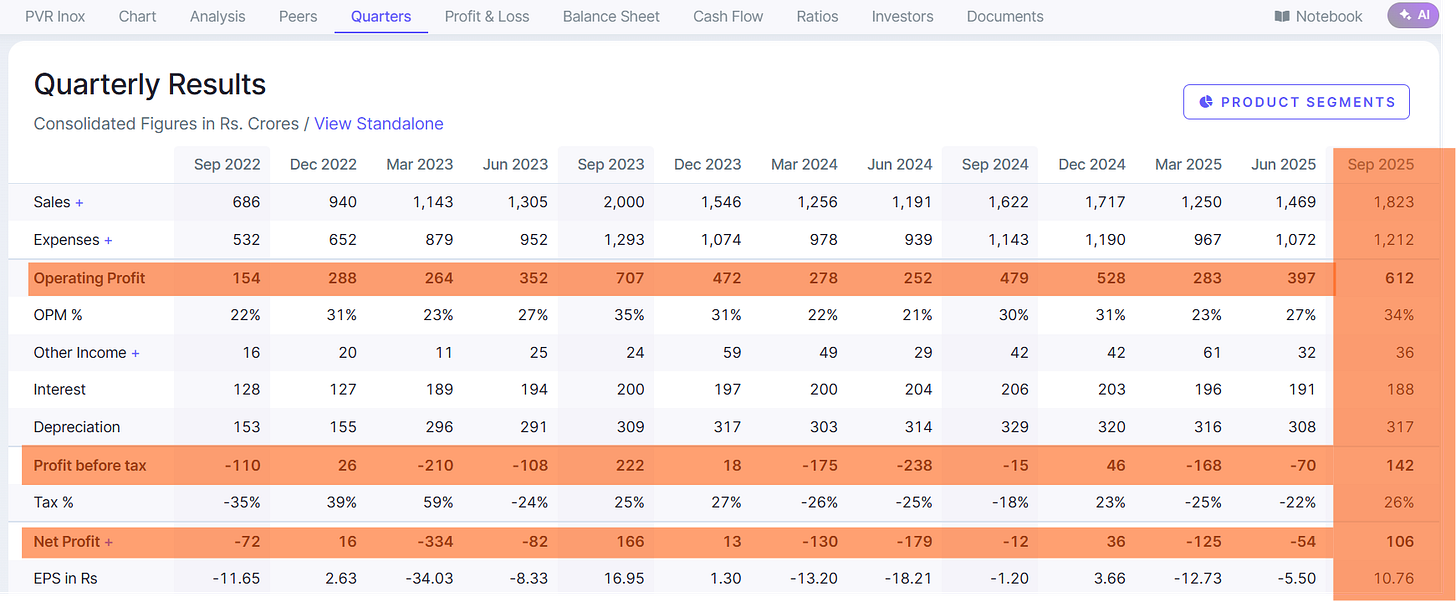

Look at the latest quarterly results [Q2FY26]

Source: Screener

Q2FY26 would rank first on revenue and second on profitability in the last 13 quarters. And what did Mr. Market do?

A Big Sell on the Rise After Good Results.

PVR Inox is a behemoth valued at INR 10,000 crore.

What if I told you that while all our attention is at the centre on PVR Inox, something is brewing on the margins?

A tiny microcap, less than 5% of the size of PVR Inox, is attempting to democratize cinema-watching in theaters for the Indian heartland?

But before moving ahead, let me share something.

Keh Ke Lunga: Ring any bells?

If you’ve watched Gangs of Wasseypur, you remember the ending not because of the violence, but because of the inevitability. Ramadhir Singh, powerful, established, untouchable for decades, lies in the hospital washroom, bleeding from bullets fired by a lean, unimposing, almost fragile-looking Faizal. A man who, for hours, we have seen absorb humiliation, betrayal, loss, and the slow-burning inheritance of a world he did not create but was forced to carry. By the time he enters that corridor with a gun in his hand, the audience isn’t shocked. It feels earned. Because the film has taken its time, it has shown you lineage. Motives. Fault lines. Old power rotting from inside. New power rising from margins that were ignored, too long. So, when Faizal pulls the trigger, your heart does not question the physics. Your brain does not compute the mismatch.

You don’t think: “Ramadhir is too big. Faizal is too weak. This isn’t how reality works.”

You simply accept it. Because the story made space for that moment. It prepared you. It asked you to believe. On screen, this would be the perfect setup. But business is not cinema. And cinema is not a strategy. Companies don’t fall the way characters do. Upstarts don’t “take revenge.” Legacies don’t lie bleeding on the floor. Markets don’t write climaxes. They write drift. Slow, unglamorous, invisible drift. And that is exactly where this story must begin.

The Rise of PVR & Inox as Ramadhir Would Explain It

You see, in every business, there is a moment when someone thinks they’ve discovered something new. But most of the time, history has already written the script. People just don’t read it. Take this whole multiplex story. Everyone remembers the glossy foyers, the popcorn tubs, the fancy lobbies. But it began in a very ordinary way.

A family with a trucking business is buying a single-screen hall in Vasant Vihar.

Source: Economic Times

Nothing heroic. Just a man trying to run a cinema. Ajay Bijli renovated Priya Cinema in 1990, and it worked. Luck and divine intervention trump strategy left, right, and centre.So was the case with Ajay Bijli, the founder.

Source: Business Standard

Sometimes, what you need most is focus. But you don’t always know where it will come from. It arrives unexpectedly; in quiet moments, tough turns, or when you least expect it.

Source: Business Standard

Success in India always attracts partnerships. So in 1995, Village Roadshow came from Australia, and suddenly Priya became Priya Village Roadshow, PVR.

Source: Business Standard

Foreign knowledge, Indian hustle. A familiar combination. By 1997, they opened Anupam in Saket, India’s first multiplex. People like to call it the start of a revolution. Actually, it was just timing. Cities were growing. Malls were coming. Families wanted something cleaner than the old halls. PVR gave them that. That’s how big players are born, not through force, but by being present when the country changes shape.

Source: Business Standard

Then Comes Scale. And With Scale, Blind Spots

Through the 2000s, PVR moved through metros the way an old political family moves through districts. Chennai today, Bengaluru tomorrow, Hyderabad next week. Screens kept increasing. Gold Class arrived. The brand got heavier, richer, and more confident. And as with every big alliance, the foreign partner eventually left. Village Roadshow walked away. ICICI Ventures filled the gap with ₹40 crore. Money makes continuity easy. People mistake continuity for strength. But it is usually just money.

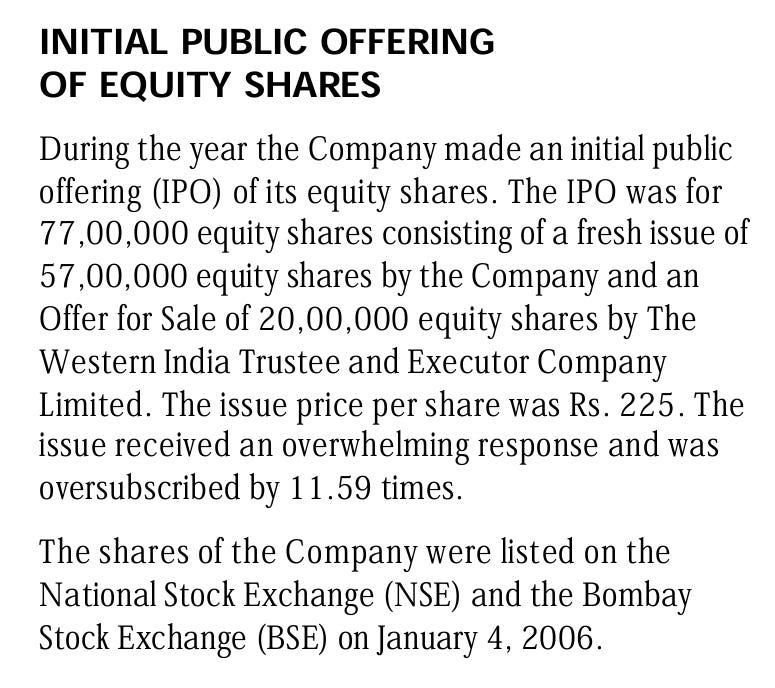

By 2006 PVR was listed.

Source: FY05-06 Annual Report

The company had become a national name. It felt inevitable. But inevitability is a temporary emotion.

Meanwhile, in Another Lane, Another Story Was Forming, Inox

While PVR was learning how to run premium halls in big cities, another group, the Inox family, was developing its own screen style.

1999: Inox Leisure is incorporated. 2002: A four-screen hall in Pune. Another in Vadodara.Then Kolkata, Goa, Mumbai. Nothing grand, nothing loud, just expansion. They had industrial gases money behind them. Old economy funding new entertainment. That’s how parallel powers grow in India: slowly, consistently, without challenging anyone directly.

Source: NDTV

In 2006, Inox was also listed. Same year as PVR. Two players, same ambitions, different territories.

Then came acquisitions.

89 Cinemas in Bengal and Assam.

Fame India between 2011–2013.

Satyam Cineplexes in 2014.

By the mid-2010s, you had just two big families in the multiplex world. PVR and Inox. Each believed they had a better sense of the audience. Whenever two powers grow next to each other without meeting, friction is just a matter of time.

Consolidation Phase

When PVR realised Inox would not fade,it did what every old power eventually does: it expanded by swallowing others.

2012: Cinemax.

2016: DT Cinemas.

2018: SPI Cinemas.

Cinemax gave them screens and locations. DT gave them NCR dominance. SPI gave them South Indian luxury. People admired the strategy. But they didn’t notice the weight increasing with each deal. Every acquisition carries responsibilities you cannot see in the press release.

And while all this was happening, PVR kept building PVR Pictures, a distribution arm to influence content. Control the film, control the screen. Old trick, still effective. By the late 2010s, PVR was clearly ahead. Inox was strong, yes, but strength in business is not about numbers alone; it is about the mindshare. PVR set the rhythm. For a while.

Then Came the One Thing No Business Plans For

Covid. Theatres shut. Rent didn’t. Staff salaries didn’t. Interest payments didn’t. You can run an empire on strategy. But you can only survive a lockdown on liquidity. Both PVR and Inox bled. Both renegotiated leases, cut costs, and raised money. Both realised the model they built over two decades could collapse in two quarters. This is where most people misunderstand disruption. It does not come from smarter entrants. It comes from old structures cracking under their own weight. COVID didn’t break the model. It simply revealed its vulnerabilities. And that is when the two rivals did what families in Wasseypur do when outsiders become a bigger threat than each other: they merged.

The Merger: The Moment Old Rivals Admit Geography Has Changed

March 2022: Boards approve the deal.

January 2023: NCLT signs off.

February 2023: PVR INOX is born.

Three PVR shares for ten Inox shares.

From enemies to partners in one announcement.

Source: Reuters

Suddenly, the combined entity has nearly 1,700 screens, 360 cinemas, more than 110 cities, and enough bargaining power to dictate terms to almost everyone around them. But power doesn’t erase fragility. It only postpones it. The merger was logical. But logic does not guarantee ease. FY23 remained messy. FY24 more volatile. FY25 even more unpredictable. One quarter profits, another quarter losses. A strong festival slate could turn things around. A few bad films could break them again. Even in 2025, footfalls rose and fell like monsoon water levels, no stability, just swings. This is the problem with large empires: their results depend on too many things they cannot control.

The Present: A Giant That Still Stands Tall, But Stands Heavy

PVR INOX today has scale, brand, legacy, partnerships, and more experience than anyone else. It also has debt. Rent. Cost structures that cannot bend too much. Customer expectations that grow faster than margins. And a model designed for India that existed between 2005 and 2018. This is not a weakness. This is age. And age, as Ramadhir knew, is not a crime. It is simply the phase when newer forces begin to rise in corners that the old order no longer observes.

PVR INOX is still the centre. But the centre does not hold attention the way it once did. It holds scale. And scale, sooner or later, becomes weight. In Wasseypur, old kings don’t fall in a day. They fade slowly, bit by bit, as smaller players occupy the lanes they no longer have time to visit.

That is the entire story of PVR & Inox. The arc of a power that grew, merged, survived, and now stands at a place where relevance must be earned again, not assumed.

But something is there on the margins that is worth noticing.

Connplex: As Faizal Would Tell It

Some stories don’t begin with noise. They begin in corners that people don’t look at. PVR and Inox grew under bright lights, malls, metros, billboards, all that shine. But Connplex Cinemas? Connplex grew the way real things grow in Wasseypur, quietly, behind older names, without disturbing anyone, without asking for permission. People think companies are born on the day their papers are filed. But the streets teach you otherwise.

On paper, Connplex looks like a company that keeps changing names.

Fohatron Power in 2015.

VCS Industries in 2018.

Head office shifted to Gujarat in 2019.

Connplex Cinemas in 2024.

If you read this like an auditor, you’ll miss the point. Names change when the old ones don’t fit anymore. When the business grows into something new. When the direction changes before the world realises it. The real story was not happening in those documents. It was happening elsewhere, in the small halls, the small towns, the small gaps the big players didn’t think were worth filling.

Connplex did not begin with a grand announcement. It began with two friends in Ahmedabad who had spent a decade learning the business from the lowest rung. One as a franchisee, one in movie marketing. Men who understood that cinema is less about screens and more about choosing the right real estate, the right partners, the right rhythm.

In the cities, multiplexes are built through strategy decks. In the towns, they’re built through judgment.

When the first Connplex hall opened in 2019, it wasn’t a chain. It wasn’t even a plan. It was a one-screen experiment in Ahmedabad. Compact, luxury-leaning, designed to test a simple idea: could a cinema be beautiful without being big? The second screen came after an eleven-month Covid pause, and from there the model found its shape. Connplex discovered that Tier-2, Tier-3, even Tier-4 towns had demand, disposable income, and hunger for the “experience” of cinema. Just not the appetite for 40,000 square feet and ₹15 crore capex.

So they inverted the model.

Instead of building a fortress, they created a neighbourhood cinema: 7,000–8,000 square feet, 3 screens, recliners, clean foyers, smart projection systems, and ticket prices that felt respectful. They brought capex down to ₹2–2.5 crore, built the hall in 60–90 days, and let local entrepreneurs take ownership through a franchise-owned, franchise-operated structure. Connplex would design, build, equip, standardise, and guide. The franchisee would run it with pride, as a business that belonged to the town, not a logo in a mall.

That is how growth happens in the margins. Not through speed, but through fit.

From Gujarat to Himachal, Telangana, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Odisha and Bihar, the numbers kept rising: 18 screens became 24, then 49, then 55 before IPO, then 83 across 9 states by late 2025. The footprint expanded quietly, in places national chains did not consider “strategic”. Connplex built Express, Signature and Luxurians formats. Each one a slightly different answer to the same question: What does this town actually want?

The economics matched the geography. Low rentals, modest staff costs, predictable monthly outgo, strong ancillary revenues from private screenings and local advertising. Nearly 55 percent of Connplex’s revenue came from cinema construction itself. A business in which they claim deep expertise. With the rest from ticketing, F&B, and revenue shares, and a margin profile that multiplex chains can only envy. With more scale, they expect better vendor terms, bigger buying power, leaner supply chains.

What makes the story striking isn’t the ambition. They speak of 10,000 screens globally. But the quiet confidence with which it’s expressed is worth noticing. Connplex isn’t trying to replace the large multiplex. It’s trying to build the cinema that India skipped while chasing malls and megastructures. A cinema that fits the towns rather than demanding the towns fit it.

USA Vs China Vs India: The Great Variance in Number of Screens

India has barely 10,000–12,000 cinema screens for a population of 1.4 billion, which works out to roughly 6–8 screens per million people. The United States has over 35,000 screens, and China has more than 50,000, giving them screen densities several times higher than India’s. The gap is not cultural; it is structural. Large multiplex formats struggle outside major cities because of high capex, high rentals, uneven urbanisation, volatile footfalls, and limited disposable incomes. Thousands of single screens have shut over the past two decades, but they have not been replaced at the same pace. The result is an under-screened country where demand exists but supply has not kept up. This is exactly the gap Connplex is building into, and exactly the constraint that makes the traditional PVR Inox model feel heavier every year. The spaces are already there. They only needed someone small enough to notice them. Connplex noticed.

Why Being Marginal Might Just Be Connplex’s Strongest Asset

Paul Graham argues that many of the world’s most important innovations come from the margins; from outsiders, not insiders. Insiders, he says, are weighed down by their own scale: big teams, big structures, big expectations. That slows them. Makes them cautious. Makes them invest more in proving legitimacy than in simply doing what works.

Connplex embodies exactly that marginal advantage. It doesn’t build 20-screen multiplexes in mega-malls. It doesn’t bet on blockbuster-heavy release cycles or premium-urban footfalls. Instead, it picks smaller towns; towns which the large chains don’t prize; and builds modest-sized, well-designed theatres: 3 screens, recliners, smart projection, manageable CAPEX, realistic rentals. It is a “smart cinema” built for a market that doesn’t need big overheads, but does need a place to watch films.

That’s the marginal path Paul Graham speaks of: cheap, lightweight, flexible, unburdened by legacy. Connplex’s expansion: 18 screens in Gujarat one year, 49 the next, then 83 across multiple states; comes not from grand plans but from filling the gaps left by the insiders. It is growing where PVR INOX has no presence, or presence but low relevance.

Large multiplexes across metros are like big companies in Graham’s model: they have scale, resources, brand, and an audience, but also inertia. Their decisions must justify capex, maintain occupancy for many screens, manage high rentals, and service debt. That weight can make them blind to the edges.

Connplex, by staying marginal, avoids that trap. It doesn’t need to fill 20 screens each night. A few full houses are enough. A compact hall, modest spend per customer, and a steady rhythm give it a kind of resilience the insiders lack. It doesn’t need to fight for weekend blockbusters; it simply offers consistent access to cinema.

This isn’t about romanticising smallness. It’s about recognising where the real structural opportunity lies. In a country where overall screen density is very low, and many towns remain unserved, the marginal space is vast. Connplex’s journey, from a one-screen luxury pilot in 2019 to 80+ screens across diverse geographies, may feel undignified to the big-screen purists. But in the quiet of Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns, it is building what the insiders forgot: accessibility, affordability, and scale-appropriate cinema.

In that sense, the future of Indian cinema may not belong to the largest multiplex chain. It may belong to those who understand the margin and treat it not as a compromise but as real ground to occupy.

The Power of The Marginal: Cues from Multiple Case Studies!

Netflix began as a DVD-by-mail service that Blockbuster dismissed as too small to matter, quietly building the model that would later transform global entertainment.

Airbnb grew from spare rooms and couches that hotels ignored, turning an informal fringe idea into a new category of travel.

Shopify empowered tiny merchants, big e-commerce players overlooked, becoming the backbone of a million online businesses.

YouTube started as a chaotic corner of amateur videos that traditional media didn’t respect, eventually becoming the world’s largest video platform.

Tesla focused on early EV enthusiasts whom automakers thought were too niche, using that marginal space to reshape the entire auto industry.

Ok, if you think that’s only possible outside India, let me share Indian examples.

BKT built a high-growth off-highway tire business in SKUs too small for large tire companies to care about, turning that ignored niche into a global stronghold.

Affordable housing finance companies scaled in loan sizes that big banks found too tiny to pursue, quietly creating one of India’s most resilient lending segments.

Pudumjee is focusing on low-volume, high-variety specialty papers that are insignificant for big paper manufacturers, using that overlooked space to craft its own moat.

Zerodha built a DIY, low-cost brokerage that the traditional giants ignored, just as Groww later expanded into Tier-2 and Tier-3 markets, Zerodha ignored that margin.

Connplex, similarly, is growing in towns and formats too marginal for PVR’s economics, using the very spaces the incumbent overlooks.

SBFC Finance is perhaps the clearest example of all, born when Aseem Dhru left two failed attempts inside HDFC Bank and built a fresh, nimble SME mortgage business from the margins, succeeding precisely because he stepped outside the weight of legacy.

The pattern is universal: The centre dismisses what the margins quietly cultivate.

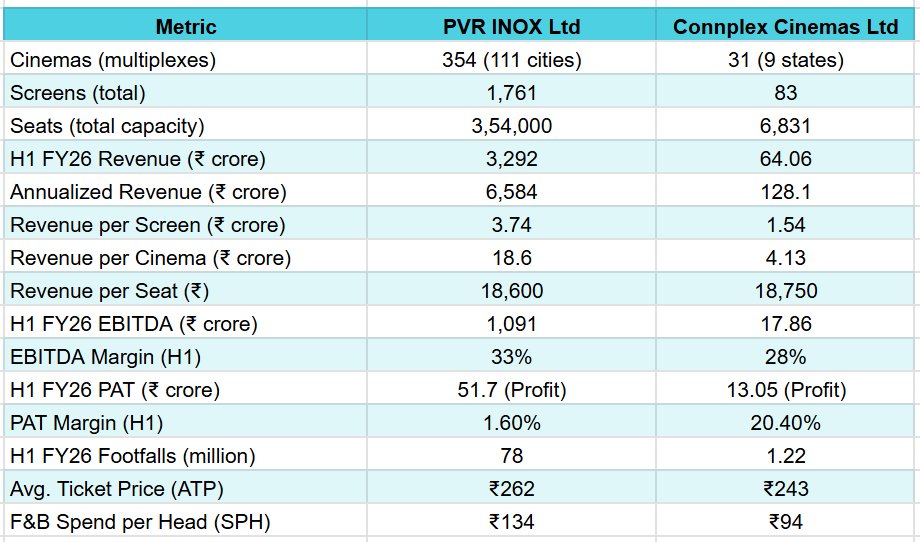

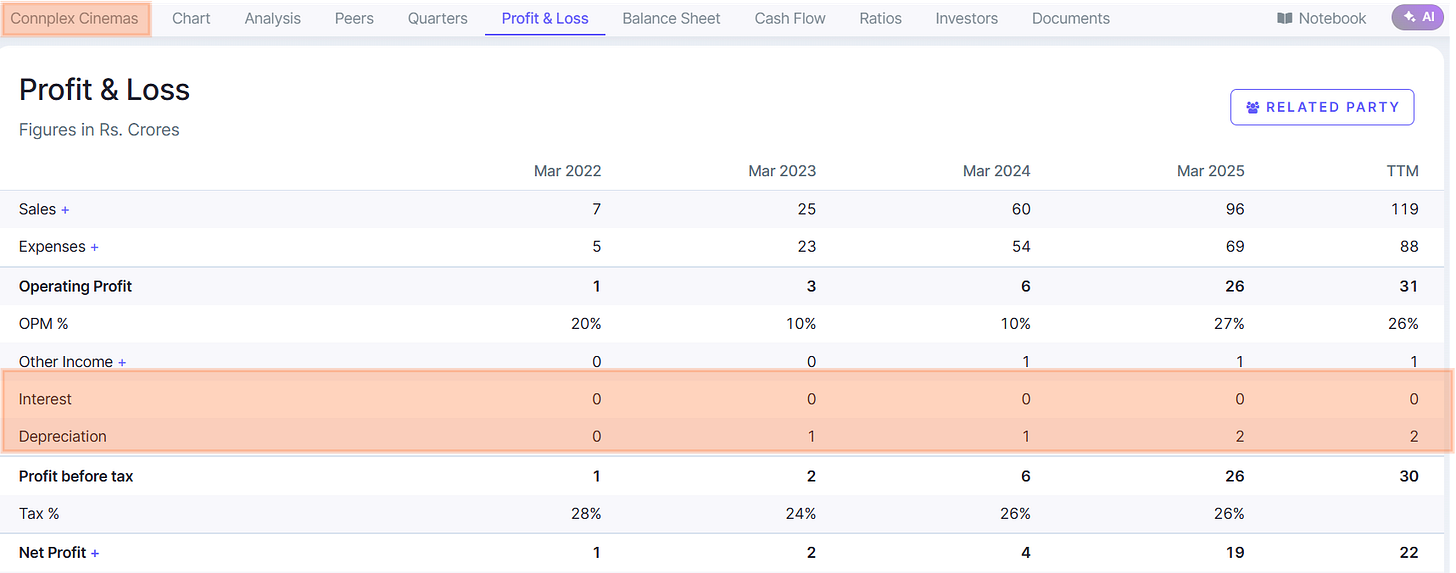

Numbers Don’t Lie

Apart from the fact that PVR INOX is nearly 50 times larger than Connplex in revenue, one detail stands out: both operate with similar average ticket prices, comparable revenue per seat, and nearly identical EBITDA margins. Yet their bottom lines diverge sharply, Connplex earns a 20% PAT margin, while PVR INOX hovers around 1.6%. Why? A quick glance at their P&L statements reveals the answer: depreciation and interest. That’s where the burden of scale shows up, and where the lightness of a capital-efficient model like Connplex quietly wins.

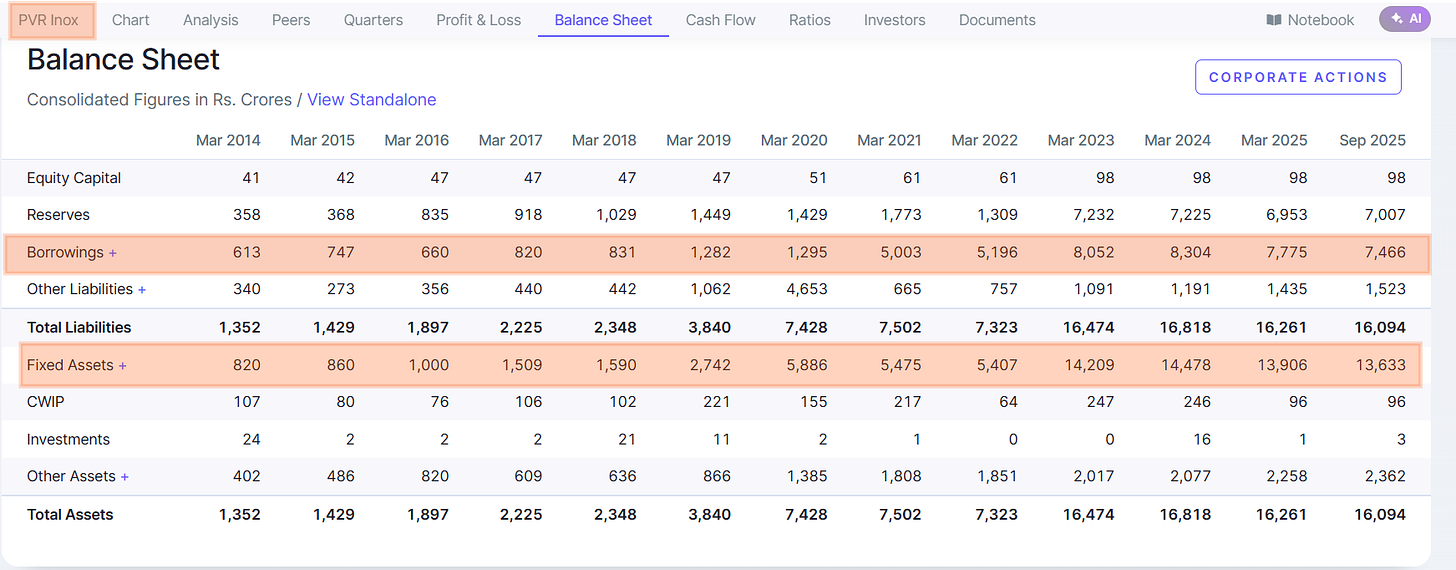

Depreciation and interest offer a window into the kind of balance sheets these two companies carry. One is heavy with assets and debt, the other is built to stay light.

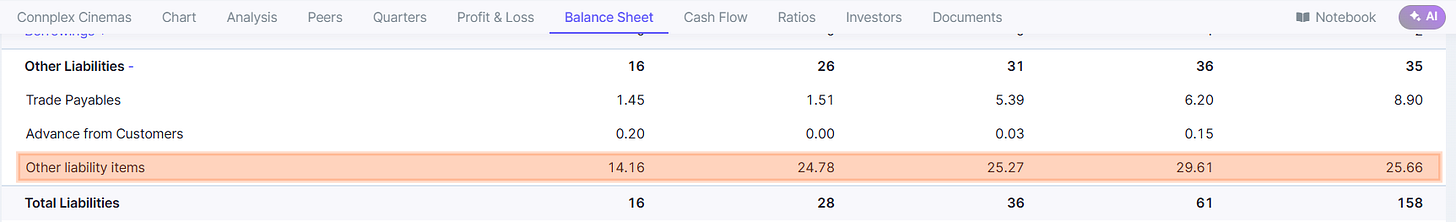

The contrast is clear: Connplex runs on an asset-light, debt-free model, while PVR INOX carries the weight of both. But the story doesn’t end there. A closer look at Connplex’s balance sheet reveals that a significant portion of its assets and liabilities sit under the “other” category, worth examining more closely to understand what’s really at play.

Most of the “other assets” turn out to be working capital items: inventories, trade receivables, and cash equivalents. But when it comes to “other liabilities,” the picture isn’t as clear. Standard screeners don’t break it down, leaving a gap worth digging into.

So, you go to DRHP.

If you do not understand the value of customer advances, read this masterpiece. Written 13 years ago. But relevant forever.

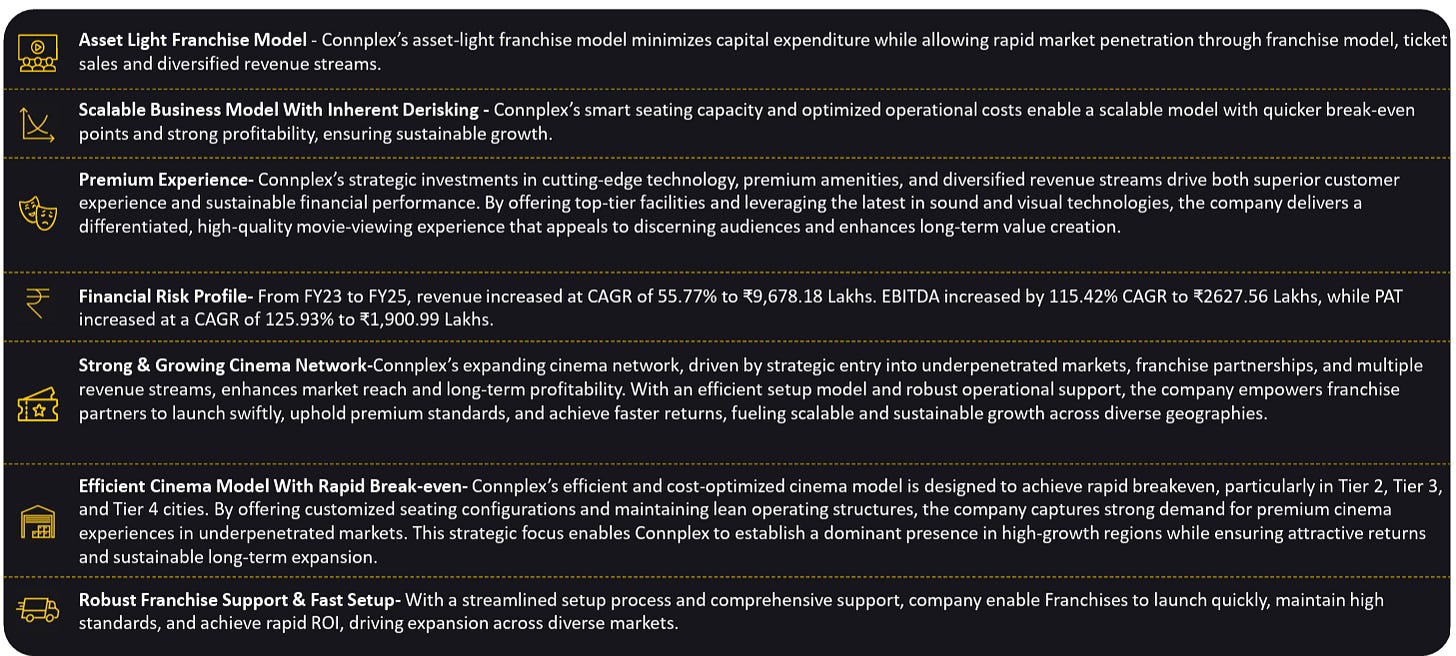

And finally, this one slide from their recent Q2FY26 presentation tells you the whole story.

The Future: That Does Not Need A Climax

“Will Connplex disrupt PVR Inox?”

It is far too early to claim anything with certainty. What we can say is that the two companies are growing in different geographies, under different pressures, shaped by different Indias. One is built for the cities that reward scale, the other for the towns that reward familiarity. One carries the legacy of expansion, the other grows in the spaces expansion leaves untouched. This is not a rivalry, not yet.

It is simply geography at work, and geography has a habit of deciding outcomes long before strategy does.

Across industries, the same pattern repeats: incumbents overlook the new entrant because it seems too small, too distant, too unthreatening to matter. The dismissiveness is almost predictable.

Paul Graham puts it neatly in his essay, and I quote:

“The really juicy new approaches are not the ones insiders reject as impossible, but those they ignore as undignified.”

Just like what Ramadhir said in this Wasseypur scene.

Thanks for reading!

P.S.

[1] No holding and no recommendation to buy or sell either PVR Inox or Connplex Cinemas.

[2] We have deep respect for business owners. They are the men in the arena. We are just armchair storywriters. Hence, we entertainingly write the story for the readers. But that should not be construed as a lack of respect for business owners.

Loved the article. Nice perspective. The points like debt servicing and depreciation were apt. I never thought that this was a hurdle for pvr inox.

Loved this article but there are pieces which are ignored here like the asset light model the company has adpated definitely it is not a near term postive but it is a long term postive.

Second is the pat margin point that you raised though margins are low & can't be reached 20% as in the case of connplex but can reach 7-10% as net debt which has reduced from 920 crore to 611 crore. Which will improve pat as gross debt is reduced.

They have closed almost 160-170 screens in the last 3 years after the merger which has impacted the growth also in total screen count.

Now can they pivot is a question only time & footfalls will.

Yes they are fragile due to it's own weight of larger presence & they need to pivot in other areas & they are experimenting & these actions how much will be successful only time will tell . These are some points when you are comparing has been missed according to me but still it is insightful as always.