Sarda Energy & Minerals Ltd

Cyclical Business | Never posted a loss | ZN Research Lab #26

They say life is a chariot. The body is the carriage. The mind is the rider. And the five horses are the senses, restless, hungry & impatient.

Most people live letting these horses run wild. The journey looks fast, but the direction is lost. But there was once a man who chose differently. He believed the chariot must be guided not by the mind, but by something deeper, the charioteer within.

Like Arjun, who surrenders the reins to Krishna, he too chose consciousness over impulse.

That choice would shape every crossroad of his life.

He began young. Brilliant, restless, full of plans. Then came the first fall, an illness that threw him off course. Days of despair followed, the mind circling in helplessness.

One afternoon, by chance, he opened a small book by an old sage. It spoke of meditation, of watching the mind instead of obeying it. Out of desperation, he tried. And slowly, he discovered a quiet he never knew existed. The stillness became his compass.

Years later, when the chariot of life moved again, he entered business. Not out of ambition, but out of duty. The factory he took over was sick, broken, and almost beyond repair. Banks had lost faith. Machines had gone silent. But when he walked through the empty shop floor, he didn’t see rust. He saw faces, workers waiting, families hoping.

A strange emotion rose within him. “I am merely the medium for their survival,” he thought.

So he stayed. He worked eighteen-hour days. Slept in the factory. Ate with the labourers. Rebuilt the business brick by brick. Within two years, the sick unit was alive again.

When people asked how he found the courage, he smiled. “When the charioteer takes the reins,” he said, “fear disappears.”

But the road wasn’t always smooth. Years later, when the steel cycle turned and numbers went red, he faced another test. Most would have hidden the losses, painted a hopeful picture. He chose the harder truth. He shut the plant early, before debt could drown the company. For a while, everyone thought he was finished.

In that silence, he meditated. He waited. He survived.

Just like Siddhartha:

“I can think, I can wait, I can fast”

Then came an intuition, one of those quiet hunches that arrive without logic. In mid-2008, as the world celebrated record markets, he felt something uneasy. “Sell everything,” he told his finance head. “No new raw material. Liquidate, even if we lose money.”

A few weeks later, the global meltdown began. His company emerged untouched. People called it foresight. He called it alignment. “When your antenna is tuned,” he said, “the signal always arrives before the storm.”

Years turned into decades. He built plants, mines, and power stations. But when he spoke to young managers, he never talked of capacity or EBITDA. He spoke of consciousness.

“Meditation,” he would say, “is the only way to make your consciousness the leader and your mind and body the followers. When that happens, your dreams become real.”

He wasn’t a mystic in robes. Just a businessman who sat still every morning before the noise began. Yet those few minutes of silence guided decisions worth crores, shaped mergers, and steadied him through crises.

These aren’t legends or metaphors. They are real moments shared by Mr Kamal Kishore Sarda, the promoter of Sarda Energy & Minerals Ltd.

In his talk “Spirituality in Business,” he speaks about how meditation and awareness became the anchor for every decision — personal and professional.

It’s a talk worth watching, not just to understand the company, but to understand the man behind it. Because before numbers and projects, there’s a way of thinking, a discipline of clarity and calm, that has quietly shaped the company’s journey.

Spirituality in Business by Sh. Kamal Kishoreji Sarda

Now, coming to the story itself. It belongs to the same sector we explored in our last blog.

Godawari Power was a masterclass in capital allocation and market cycles. Read it here if you have not yet:

This one is a class apart. It is about a company that has consistently moved beyond those cycles, a business that, as far back as the data goes on Screener, has never reported a loss, even at the net profit level.

Of course, Sarda Energy & Minerals Ltd. is also not a microcap anymore, but its story began as one. A small, struggling unit that transformed itself through decades of patience, discipline, and self-reliance. And in that transformation lies a timeless lesson for every investor.

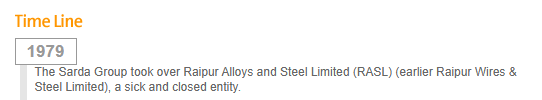

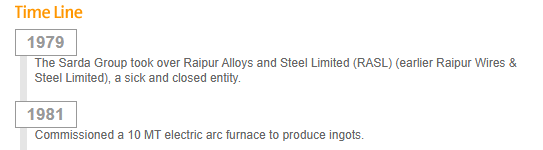

In the 1970s, on the outskirts of Raipur, there was a small rolling mill that had almost stopped breathing. The furnaces were cold, the gates rusted, the place forgotten. It was called Raipur Wires and Steel.

By the late 1970s, the plant was officially defunct. But in 1979, the Sarda family stepped in. Led by a young and determined Kamal Kishore Sarda, he took over the ailing unit and renamed it Raipur Alloys and Steel.

Source: Company Website

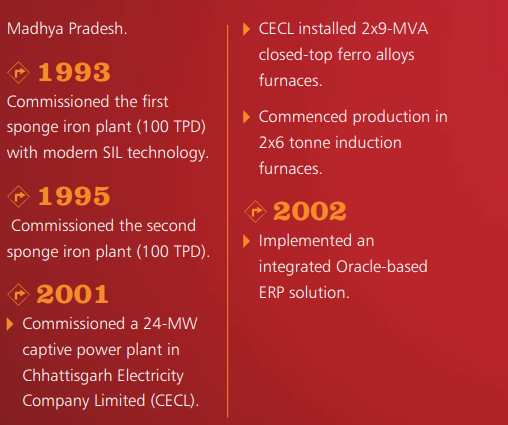

The early years were about survival. Old machines were repaired, new ones were added, and slowly the hum of production returned. By 1981, a 10-ton electric arc furnace had been installed, marking the company’s return to steelmaking. Three years later, a continuous casting machine came in, one of the first in the region. The plant that once sat in silence now buzzed with the rhythm of molten metal and rolling steel.

Source: Company Website

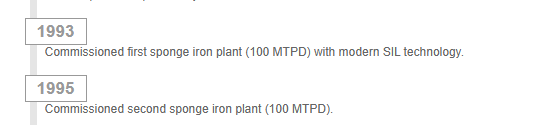

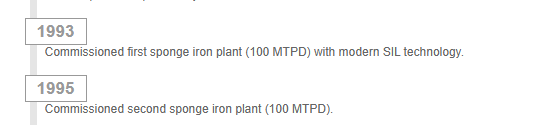

But the Sardas knew that technology alone would not be enough. The real test lay in raw material security. Most small steel players struggled because they relied on expensive scrap. The Sardas wanted independence. They decided to produce sponge iron in-house, a move that few in the region had attempted at the time.

Sponge iron is made by reducing iron ore without melting it, giving a porous, clean form of iron that can be used directly in furnaces. It’s cheaper and more consistent than scrap. In 1993, the company built rotary kilns. It produces 100 tonnes per day to make sponge iron. It was a bold step, and it worked. The plant began using its own sponge iron to produce billets and rolled steel, cutting costs and improving margins.

Source: Company Website

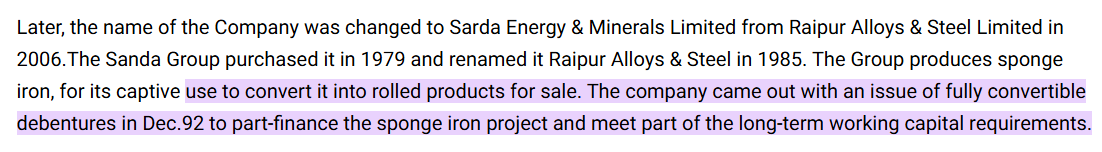

To fund this expansion, the company turned to investors. In 1992, it issued convertible debentures, asking the market to back a turnaround story.

Source: India Infoline

The money helped build the kilns and revive working capital. By 1995, success was visible. A third kiln was added, and the capacity doubled.

Source: Company Website

The company also started refining its steel with new techniques like oxygen lancing and ladle refining, which improved quality and productivity.

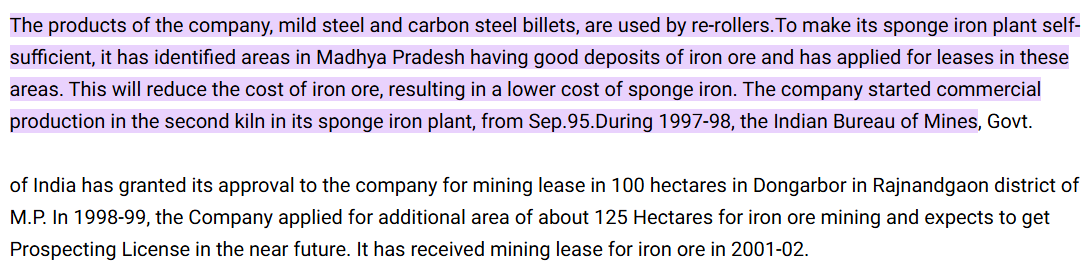

Through the 1990s, the Sardas followed a simple rule: own what matters most. Steelmaking is a business of cycles, and the only way to survive them is to control your inputs. So they began chasing mining rights for iron ore. By 1997–98, they secured a 100-hectare lease in Dongarbore, Rajnandgaon, and soon applied for another 125 hectares nearby. It would take time before mining began, but the intent was clear. The company wanted to make steel from its own ore.

Source: India Infoline

What started as a shut-down mini-mill had become a stable and growing steel operation.

The next focus was power. The group commissioned a 24-megawatt captive power plant under Chhattisgarh Electricity Company Limited (CECL). Alongside, CECL also installed two 9-MVA closed-top ferro-alloy furnaces, and the parent company, Raipur Alloys & Steel, started production in two 6-tonne induction furnaces.

At first glance, it looked like a cluster of small technical upgrades. In truth, it was the beginning of something larger, a self-sustaining ecosystem. The Sardas were quietly solving a problem that kills most small steelmakers: dependence. Power shortages, expensive alloys, and outsourced melts all stall production overnight.

Source: 2008 Annual Report

It changed everything. While many peers suffered from rising tariffs and outages, SEML had uninterrupted, low-cost power. The furnaces could run at full capacity, and if there was any surplus, it could even be sold to the grid.

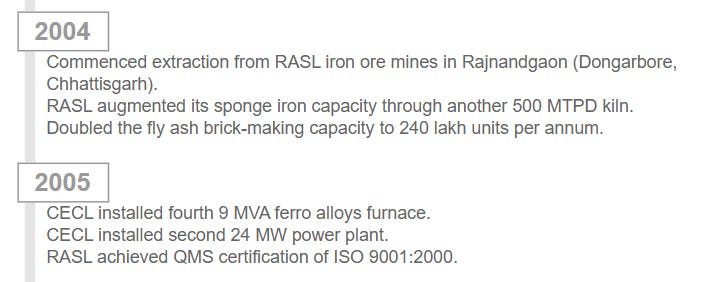

By 2004, another iron ore lease was added nearby. At the same time, the plant added another 500-tonne-per-day sponge iron kiln, lifting total capacity and tightening control over input quality. Even the byproducts found a purpose. Fly ash from the power plant, a nuisance for most factories, was turned into a resource. The company doubled its fly-ash brick capacity to 240 lakh units per year, selling what others threw away. It was the same mindset seen across the organisation: use everything, waste nothing.

In 2005, the integration deepened further. The power arm, CECL, installed a second 24-MW thermal power plant, doubling the base that fed the furnaces. Alongside came a fourth 9-MVA ferro alloy furnace, adding muscle to the alloy division.

The pieces were falling into place. The company was now mining its own ore, producing its own power, and making its own steel. Integration was complete.

Source: Company Website

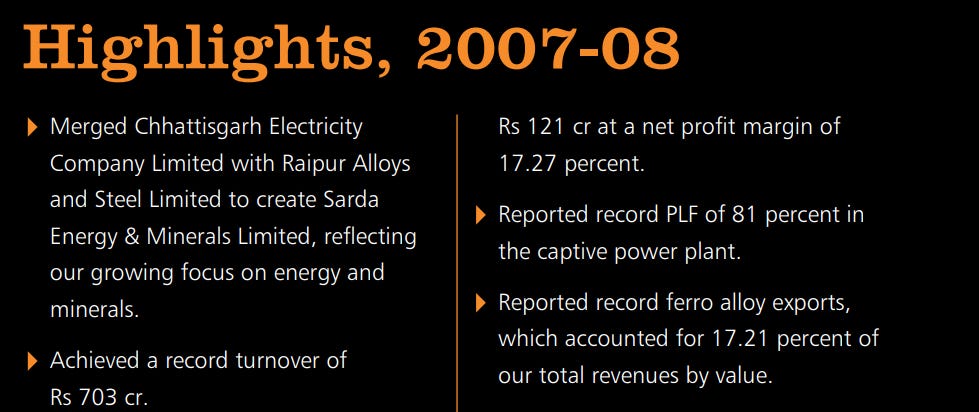

In 2006, Raipur Alloys & Steel became Sarda Energy & Minerals Ltd. In 2007–08, SEML merged Chhattisgarh Electricity Company and Raipur Gases into itself. Everything was brought under one roof, both in structure and spirit.

Source: 2008 Annual Report

The Sardas had spent nearly three decades building layer upon layer of strength. They didn’t chase glamour or speed. They just built quietly, piece by piece, until the foundation was unshakable. The next decade would test how far that foundation could take them.

Now, expansion needed money, and SEML was ready to raise it. In 2007, the company issued 44.7 lakh shares at a premium of ₹180 per share, bringing in around ₹85 crore from IDFC and Lehman Brothers’ Mauritius arm. It also issued warrants for possible future investment. The funds helped build the pellet plant and add new capacity.

Source: India Infoline

Steel capacity was the first to rise. By 2008, billet production had jumped from 1,40,000 tonnes to 2,40,000 tonnes per year after adding two new induction furnaces.

Source: 2008 Annual Report

Sponge iron capacity grew from 2,10,000 to 3,60,000 tonnes with a new 500-tonne-per-day kiln.

Source: India Infoline

The expansion also created room for innovation. Iron ore fines from mining, which would otherwise be waste, were turned into a new product. In April 2010, SEML commissioned a pellet plant of 0.6 million tonnes per year at Siltara. These pellets, small marble-like balls of concentrated iron, became a key feed for the sponge iron kilns. The company used modern grate-kiln technology, one of the few in India to do so at the time. The idea was simple but powerful: use every part of the ore, waste nothing.

Source: Annual Report 2010

Now, scale spreads cost; scope multiplies opportunity. The pellet plant and alloy furnaces were not random expansions. They were acts of optionality. Nassim Taleb uses that word for systems that have many ways to win but limited ways to lose.

By 2010, SEML’s Raipur complex had become a self-contained industrial ecosystem where every process fed another and nothing went to waste.

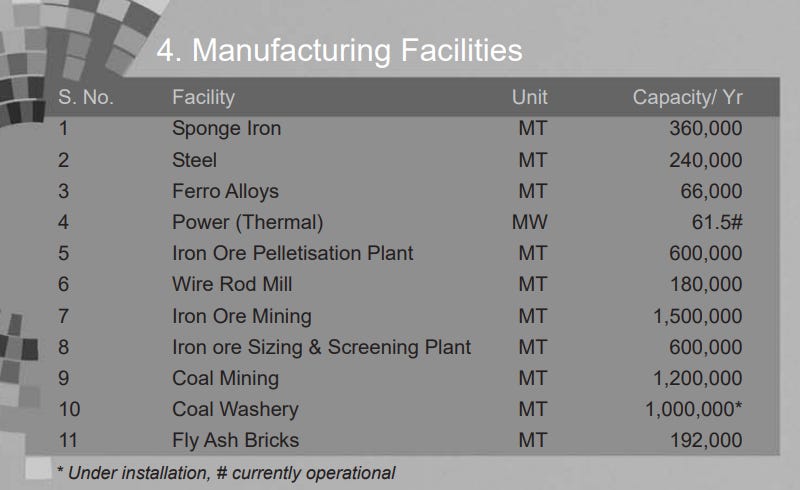

The sponge iron unit produced 3,60,000 tonnes a year, feeding the steel furnaces that turned out 2,40,000 tonnes of billets. The ferro alloy division, running at 66,000 tonnes per year, had grown into one of the region’s most efficient exporters, powered by 61.5 megawatts of captive thermal capacity.

The pellet plant, with 6,00,000 tonnes annual capacity, converted iron ore fines into uniform feed for sponge iron kilns. The wire rod mill, at 1,80,000 tonnes, rolled billets into long coils that often went straight into SEML’s own wire-drawing units.

Upstream, the iron ore mine in Rajnandgaon produced about 1.5 million tonnes a year, supported by a 6,00,000-tonne screening plant.

Source: Annual Report 2010

By 2013, SEML was no longer a small Raipur mill. It was a global exporter, an integrated steel and power producer, and a case study in how steady reinvestment can transform a local enterprise into an industrial force.

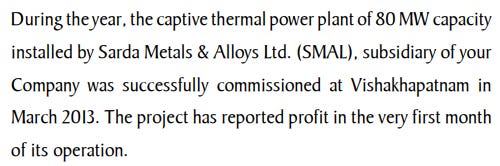

But the real leap came when SEML decided to step outside Chhattisgarh. In 2013, it set up a greenfield ferro alloy plant near Visakhapatnam under a subsidiary named Sarda Metals & Alloys Ltd (SMAL). It had an 80 MW captive coal-based power plant.

Source: 2013 Annual report

While SEML was building new capacity, the rules of the game were changing. In 2014, the Supreme Court cancelled nearly all private coal block allocations made over previous decades.

Source: Duanemorris

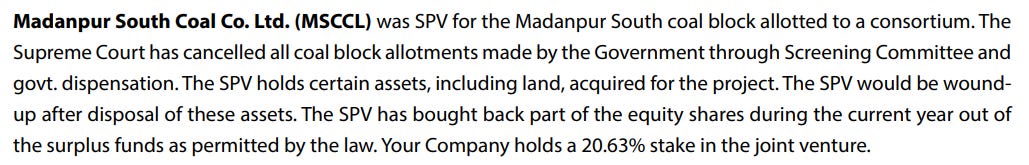

SEML’s Madanpur South coal block was among those cancelled. Years of preparation and investment were wiped out with a single verdict.

Source: Annual Report 2015

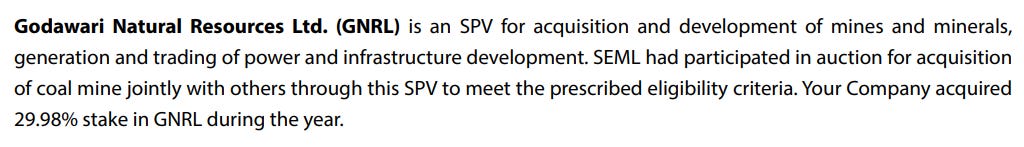

Most companies would have sulked or slowed down. SEML did the opposite. Anticipating the shift to auction-based allocations, it had already taken a 29.98% stake in Godawari Natural Resources Ltd, an associate of another Chhattisgarh steelmaker (yes, you guessed it right).

Source: Annual Report 2015

Together, they planned to bid for new blocks under the auction system. It was a textbook case of turning adversity into advantage. When the coal-block allocations were cancelled, most companies froze. SEML adapted. This is what Nassim Taleb calls Antifragility, a system that gains from shocks. It had cash, speed, and readiness. Liquidity, often dismissed as idle money, turned into a weapon. In crises, cash is not laziness; it is courage.

By 2019, the rhythm of Sarda Energy’s operations had become steady and confident. The Raipur complex was running close to full tilt. Sponge iron production touched new highs 92,500 tonnes in a single quarter, the best in the company’s history.

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

Every part of the chain seemed to be working in sync. Only a temporary 25-day shutdown of one captive power plant disturbed the flow, but even that became an exercise in efficiency. When it came back online, power generation hit a record 287 million units, showing how tightly integrated energy and metallurgy had become inside the Siltara gates.

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

The mood across the steel sector, however, was uncertain. The global slowdown and NBFC crisis had softened demand, and prices of billets and wire rods slid throughout the year. Yet SEML’s margins held up better than many peers because of its captive model. The company was now debt-light and generating enough internal cash to refinance loans at a lower cost. By September 2019, it was practically net-debt-free at the standalone level, with a consolidated debt-equity ratio below one.

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

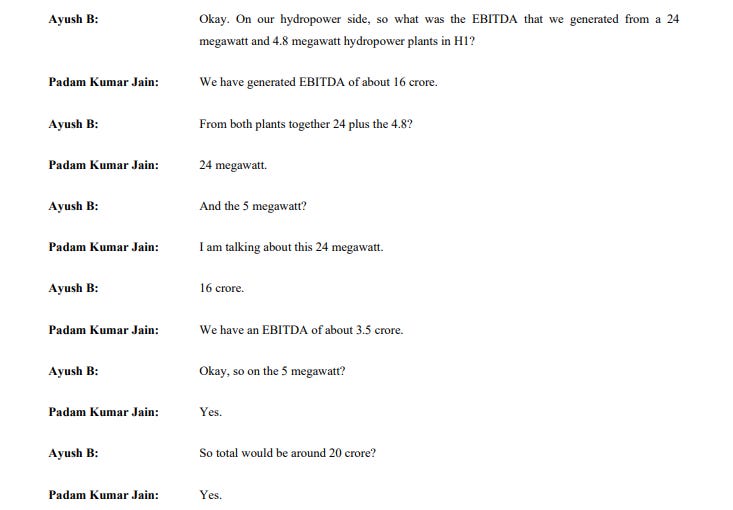

What really stood out in this phase was the gradual emergence of a second growth engine, hydropower. The 24-megawatt Chhattisgarh hydro project was already contributing steady cash flows, generating around ₹16 crore EBITDA in six months, while another 5-megawatt plant added another ₹3.5 crore

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

But the real anticipation was for Sikkim. The company had almost finished its 115-megawatt Sikkim hydro project, after years of delays caused by monsoon damage and road blockages. By early 2020, the site was buzzing with final erection work. The entire equity had been infused, long-term PPAs were in place, and commissioning was expected in the first quarter of FY21.

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

That project, Madhya Bharat Power Corporation, was a milestone. Once operational, it was expected to generate nearly 400 million units annually, translating to an EBITDA of roughly ₹180–200 crore a year. The tariff, expected in the range of ₹5.50 to ₹5.70 per unit, would place it comfortably within the regulated renewable bracket

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

The economics were clear: around ₹1,400 crore of project cost, ₹900 crore of debt, and an interest rate likely to fall once refinancing kicked in after commissioning.

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

The plant would take two years to fully stabilise and turn PAT-positive, but even in its first year, the project could throw up ₹80–100 crore in cash flow after servicing interest, a strong addition to group earnings

Source: Q2FY20 Concall

Meanwhile, at the steel complex, SEML kept refining the smaller details, debottlenecking the pellet plant, building inventory to ride price cycles, and expanding ferroalloy operations. By late 2019, both furnaces at Sarda Metals & Alloys (Vizag) were running again after relining, operating at full capacity.

By the time the calendar turned to 2021, Sarda Energy had quietly completed a transformation that had been more than a decade in the making. The massive Sikkim hydroelectric project, once a distant dream battered by monsoons and landslides, was finally approaching the finish line. Nearly ₹1,400 crore had gone into the hills, poured into tunnels, penstocks, and turbines. All equity was in place, and the final cables were being drawn. The management had waited long for this moment, and their patience was about to pay off.

In April 2021, the 115-megawatt Sikkim hydropower plant was synchronized to the grid. For the first time, the sound of rushing water from the Teesta tributary translated into electrons on SEML’s balance sheet.

Source: Q4FY21 Concall

The project’s long-term PPA (Power Purchase Agreement) was secured, pegged around ₹5.50–₹5.70 per unit, comfortably within the regulated renewable band. With that, SEML entered a new orbit. The plant was designed to generate around 400 million units annually, which at those tariffs translated to ₹180–200 crore of EBITDA steady, inflation-protected cash flows that could last for decades

Source: Q4FY21 concall

Hydropower brought something the steel business never could: predictability. Steel prices could swing, iron ore costs could spike, but water flowing down a mountain kept its rhythm. The company had effectively built itself a financial shock absorber.

Source: FY20 Annual Report

This was also when SEML’s balance sheet began to show real strength. Despite adding over ₹900 crore of project debt, the net debt-to-equity ratio stayed below 1x. The company was still net-debt-free at the standalone level, and group borrowings were fully backed by operating assets. Refinancing talks began soon after commissioning, aiming to cut interest rates by 1–1.5 percentage points, as lenders now saw a de-risked, fully operational hydro project rather than a construction site.

Source: Q4FY21 Concall

Source: Q4FY21 Concall

Back in Raipur, the core operations of steel and alloys continued to hum. The integrated plant had reached maturity, with the highest-ever production of sponge iron, billets, and wire rods through FY20. Ferroalloy output rose as both furnaces at Sarda Metals & Alloys, Vizag, returned to full capacity after relining. The company had also built up 40,000 tonnes of pellet inventory, a move that looked prescient when prices rose sharply in 2020

Source: Q3FY20 concall

Globally, steel demand was recovering from the pandemic lows, and SEML’s mix of captive mines and captive power ensured stable margins even when input prices climbed. The group’s total thermal power generation crossed 440 million units, its highest ever. Hydro output jumped thanks to extended monsoons, with 97 million units produced in nine months of FY20, rising further after Sikkim came online.

Source: Q3FY20 concall

Source: Q3FY20 concall

The Sikkim project began contributing a full year’s performance, pushing consolidated EBITDA to new highs. Hydro became a core profit driver, alongside ferroalloys. Management discussions began hinting at a possible demerger of the power assets into a separate subsidiary, once the hydro portfolio stabilized, a move that could unlock value and give clearer visibility to investors on the energy side of the business

Source: Q2FY20 concall

Interestingly, even as others in the industry chased capacity, SEML kept its focus inward. It didn’t rush into new greenfield projects. Instead, it used this phase to strengthen its moat, renew mining leases, fine-tune efficiency, and prepare for the next cycle. The philosophy was simple: build cash before expansion, not after.

In many ways, this period reflected what Howard Marks calls “Second-Level Thinking”. The ability to look beyond surface trends and prepare for what others overlook. Where peers saw cyclicality, SEML saw asymmetry. It used boom years to deleverage and diversify, ensuring that when the next downcycle came, it would be sitting not in a furnace of debt but in the calm hum of hydro turbines.

By the close of FY23, SEML was generating power from both fire and water, thermal, hydro, and soon, something bigger. The stage was set for what would become the company’s boldest act yet: the acquisition of SKS Power.

Source: Business Standard

By 2023, Sarda Energy was standing at the edge of a new horizon. The furnaces in Raipur and the turbines in Sikkim were running strong, but the company was thinking bigger, beyond captive power, beyond self-sufficiency. It was ready to scale its energy play. The moment came through an opportunity that few could dare to take, a large, stressed asset waiting to be revived.

This was SKS Power Generation (Chhattisgarh) Ltd, a 600-megawatt coal-based plant located in Raigarh.

Source: Q3FY23 concall

The asset had solid bones two 300 MW units commissioned between 2014 and 2017 but it was trapped in financial distress after years without long-term PPAs and expensive coal procurement. In 2022, SKS landed in insolvency. For SEML, whose coal mine sat barely seventy kilometres away, this was an alignment too precise to ignore.

Source: Q1FY24 Concall

This acquisition would not just add capacity, it would reshape SEML’s business mix. The board approved the resolution plan under IBC, and by August 2024, SEML’s offer, around ₹1,950 crore, was accepted by lenders. Within days, the entire amount was deposited in escrow. The transaction closed swiftly.

Source: Q1FY24 Concall

Source: Q1FY24 Concall

The numbers told the magnitude of this step. SEML had used roughly ₹575 crore of its own cash and raised ₹1,375 crore of long-term debt to fund the deal. Even after the acquisition, net gearing stayed modest, a rare case where a company could double its power base without over-leveraging

Source: Q2FY25

Source: Q4FY25

The logic was straightforward: SEML had cheap, captive coal from the Gare Palma IV/7 mine, and SKS needed coal. A perfect fit. The integration was immediate. Plans were initiated to expand the mine’s capacity to 1.8 MTPA, and later to 5 MTPA, along with a coal washery and a dedicated railway siding to move coal directly to the SKS plant.

Source: Q4FY25

The company also moved fast to secure buyers. SKS already had a mix of short and medium-term PPAs covering about half its output. SEML’s target was to lift the plant load factor (PLF) to 80% by ensuring fuel certainty and adding new PPAs.

In Q1 FY26, PLF already rose to 90% at the main thermal unit, compared to 71.6% in the same quarter the previous year

Plant Load Factor (PLF) basically tells us how much of a power plant’s total capacity is actually being used. If a 600 MW plant runs at 90% PLF, it’s producing almost 540 MW on average, day and night.

If it runs at 70%, it’s only producing around 420 MW.

The higher the PLF, the more electricity you generate and sell and the more money you make without really increasing your fixed costs.

The difference was visible in the numbers. For the first time, SEML’s quarterly performance was led not by steel, but by electricity. As Mr. Pankaj Sarda put it, “Hydropower generation grew by 37% year-on-year, supported by early monsoon. Our IPP thermal power plant achieved a significantly improved load factor due to operational efficiency.”

The balance sheet, once dominated by metal, was now being powered by electrons.

The SKS acquisition also shifted perception. SEML was no longer just a metals company with captive power. It had become a genuine energy and resources enterprise, producing electricity from hydro, thermal, and soon, solar.

Of course, there were clouds too. The SKS acquisition faced ongoing appeals at the NCLAT and the Supreme Court, with competing bidders challenging the process. The management acknowledged the litigation but remained confident.

The lenders had supported SEML’s plan, and the plant’s operations were running uninterrupted under SEML’s ownership.

Financially, the impact was transformative. Net debt was comfortably serviceable, backed by operating cash from hydro and thermal assets. The internal coal advantage made SEML’s cost per unit among the lowest in the merchant power market, a moat few could replicate.

Now, if you trace it all the way back, the journey feels almost poetic. A forgotten rolling mill in Raipur found life again in the 1970s, and fifty years later, the same family revived a 600 megawatt power plant that had gone silent. What began with steel ended with energy, but the thread that connected both was stillness.

Most people build companies by chasing what can be seen: scale, profit, size. He built his by listening to what cannot be seen, intuition, rhythm, and silence. Meditation was not a retreat from business; it was the root of it. Every morning, before the world began to rush, he sat quietly, tuning the chariot within.

When the global crash came in 2008, he had already stepped aside from risk. When the coal block cancellations came, he turned loss into opportunity. When SKS appeared in insolvency, he saw not a dying asset but an echo of his own beginnings. To him, life and business were the same experiment, to see whether consciousness could guide the horses of mind and senses without losing balance.

Sarda Energy’s story, then, is not just about furnaces, mines, or megawatts. It is about how calm can compound faster than capital. Steel gave it strength, power gave it scale, and stillness gave it direction. In the end, the man who once meditated in a silent factory now runs one where silence itself has become power, and that, perhaps, is the truest form of energy.

Disclaimer: Zen Nivesh - No Holding, Harshal/Writer - No Holding. No Recommendation to Buy/Sell.

If you have been reading our blogs regularly, you would know that there was an early access available especially for our Substack subscribers to get a chance to onboard into our micro-cap focused Zen Nivesh Stock Advisory Services [ZNAS].

As all good things, that has come to an end. :)

We are happy to share some numbers.

~1000 investors joined our waitlist.

~150 members onboarded to our platform.

We are still running our FESTIV discount offer on our Zen Investing Club subscription. Check that out here.

And last but definitely the most important thing.

Happy Dhanteras!🙏🙌👏

Wishing you a Dhanteras full of abundance and good fortune.🤗

May your wealth multiply manifold.

Just remember to grow your mind and conscience first to be able to handle the growth in wealth.🙏

Pure Gold Harshal Bhai!

Reading so late in the Night - thoroughly enjoyed / appreciated your Blog on Sarda Energy ....

But it lead me to thinking more - as to Y I am having that connect with your past few Blogs - every single one of them exceedingly good BTW.

And then it hit me - When I read through your Blogs, because of your writing Style and the due diligence done and then putting the whole thesis in a Story format sort of - I now have an emotional connect with the Management and feel their pain/hardships throughout their Journey - and what it has taken for them to reach the current standing/position! I better appreciate that and that stays!

This I guess is Such a Fantastic a Win for me personally speaking - because by nature, I chase Momentum and will Not hesitate to Sell my position if the numbers don't align or I see headwinds ahead! More Probability of that happening in underlying Businesses which are Hard-Asset-based and have Cyclicality built-in.

But because of your Writeups, I now have that intangible connect with the Mgmt and sort of belief that this too shall pass - that probably, just probably I might give the Mgmt more time to perform - and gain myself in return because of LT Holding ...

Harshal Bhai - Please keep your Blogs coming - Already looking out for the next one ... :)

Very well written! I can see the work which would gone in writing this blog. People usually call such businesses as boring; but the way you have written it, it was very interesting to read.