Godawari Power & Ispat

Steel | Capital | Temperament | ZN Research Lab #25

There is a simple rhythm to metals.

Good prices invite money. Money builds capacity. Capacity kills prices. Prices fall until Music (investments) stops. Then scarcity does its quiet work, and the cycle turns again.

Edward Chancellor calls it the capital cycle. In plain words, the chase for high returns often destroys the very thing it chases. Because in the metal business, you don’t just make steel, you live through cycles of greed and discipline. The best investors don’t try to predict the price of iron; they try to predict the behaviour of capital. That’s the real cycle Edward Chancellor talks about. The rhythm between abundance and scarcity.

But before I move ahead, here’s something you must know. Do you remember the 4 pillars of our ZN playbook?

No worries. Let me refresh it quickly.

Turnarounds / High-Convexity - improving ROE/ROCE flywheels.

Special Situations - corporate actions, mispricings, and catalysts.

High Growth / Industry Tailwinds (Yard Investing) - riding secular shifts, not headlines.

Deep Value - company trading at a discount, with patience as a moat.

If you want to have all 4 ZN playbook pillars in one, check this out:

Solara Active Pharma Sciences: The Reset

Every once in a while, markets hand you a setup that looks linear, but if you tilt your head a little, the payoff is convex.

There is a reason I took a break from the metal rhythm and shared this.

~900 smart investors have joined the waitlist of our micro-cap-focused stock advisory.

~600 of them wish to have early access to ZN Playbook.

Early access begins this weekend. This is your last opportunity to join. Before the rest.

Time to be back on the blog.

The rhythm of the metals. :)

I am going to tell you the story of a company that is living inside this rhythm. A company in the steel sector, where every boom carries the seed of the next slowdown, and every slowdown hides the chance for a revival. Most players fall into this chakravyuh of the capital cycle and never find their way out. But there is a way out, not obvious, not glamorous, and rarely quick. It lies in discipline, timing, and the quiet art of capital allocation.

To survive this rhythm, a steelmaker needs two things. Control over inputs that keep costs steady when prices wobble. And the judgment to slow down when the crowd speeds up. The first is engineering. The second is temperament.

We at Zen Nivesh have a razor-sharp focus on the microcap space (less than ₹3000 Cr market cap businesses), but today the company I am covering sits slightly above that range. The reason is simple. Let us try to understand what exactly it did that helped it survive every capital cycle of the past, and more importantly, whether it is efficient enough to do it again. If we understand this, we can try to find a similar pattern in this sector. And maybe, eventually, find a microcap worth studying that falls in the same pattern.

Technical patterns are easy to spot and measure in terms of successes and failures. A few hours or a few days, or maybe a few months. And you know whether you were right or wrong. Investing patterns like the one I am sharing with you here are hard to spot and measure. It is not a matter of days or weeks. Often, multiple months or years pass by. And that’s why it is very difficult to figure out the proportion of luck and skill/research that played out. We try to cover different investing patterns at Zen Investing Club [ZNIC].

So, let’s start understanding this ₹16,000 beast to hunt for similar opportunities in the microcap space.

Godawari Power & Ispat Ltd began its journey in 1999 under the leadership of B. L. Agrawal, a first-generation entrepreneur from the Raipur-based Hira Group. The idea was simple but powerful. Build a steel business that could stand on its own feet. In other words, make everything in-house.

Think of it this way. Most steelmakers buy their raw materials and power from outside. GPIL wanted to own that entire chain. Like a bakery that grows its own wheat, mills its own flour, and bakes its own bread. That idea became the foundation of the company’s model. Integrated steel player.

Source: Company Website

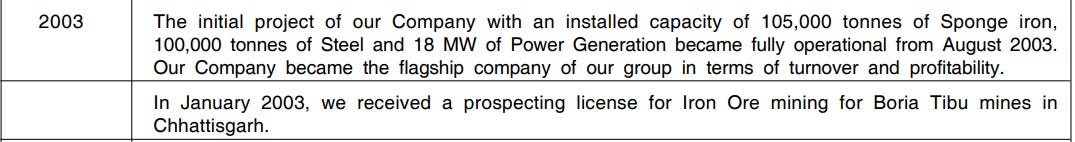

The company started with a sponge iron plant, which produces what is called direct-reduced iron, the main raw material for steel. Alongside it came a billet casting facility and a captive power plant to supply electricity to its furnaces. By 2001, the first sponge iron kiln was running. By August 2003, the initial project had reached full capacity, about 1 lakh tonnes of sponge iron, another 1 lakh tonnes of billets, powered by a 10 MW captive plant.

Source: Hira Group website

There’s a phrase in investing called the circle of competence. It simply means doing what you understand deeply and avoiding what you don’t. GPIL’s early years were a perfect reflection of that. It didn’t chase fancy products or futuristic tech. It stuck to what it knew: iron, steel, and power. And because it understood those levers inside out, it could build efficiencies that outsiders would overlook.

This success made GPIL the flagship company of the Hira Group. It could now supply billets and power to the group’s rolling mills, closing the loop inside the family. Around the same time, in January 2003, the company also secured a prospecting license for an iron ore deposit at Boria Tibu in Chhattisgarh. That small step would later prove important because it laid the groundwork for raw material self-sufficiency.

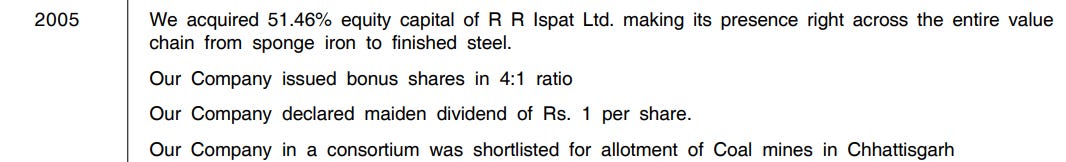

Source: RHP

Encouraged by early profits, GPIL began expanding in 2004. It doubled its sponge iron capacity, added another one lakh tonnes of billet casting, and built a second power plant. It also moved higher up the value chain by installing a ferro-alloy furnace of 16,500 tonnes per annum, used to make alloys like silico-manganese, and a wire rod mill of 60,000 tonnes per annum.

Source: Hira Group website

By 2005, GPIL had become a modestly integrated steel operation. From iron ore at one end to finished steel wires at the other, it covered almost the full journey. That same year, the company acquired a majority stake in R. R. Ispat, which owned rolling mills. This meant GPIL’s billets could now be rolled into finished products within the same group. To put it simply, GPIL had built a mines-to-metal business. It could mine its ore, make sponge iron and billets, generate its own power, and roll finished products. This kind of integration brings stability in both cost and supply. It is like a farm-to-table restaurant that grows its own vegetables and serves them fresh to the customer.

Source: RHP

In 2006, GPIL decided to go public. And the new growth journey began!

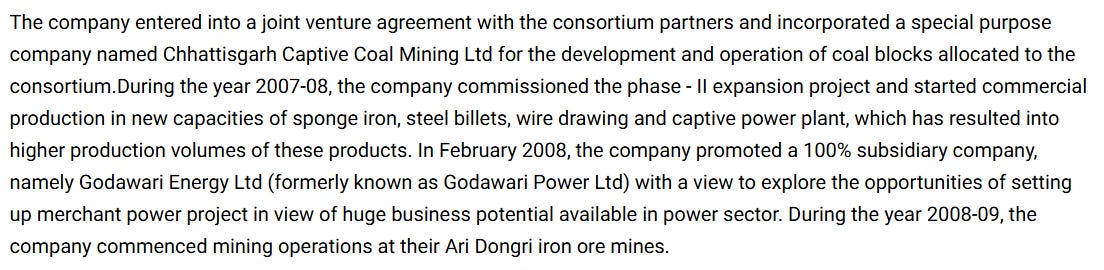

With funds from the public issue, Godawari Power and Ispat entered a new phase of growth. The late 2000s were all about control, not in the sense of dominance, but in the sense of self-reliance. In steelmaking, control over raw materials decides who survives in a downturn and who does not.

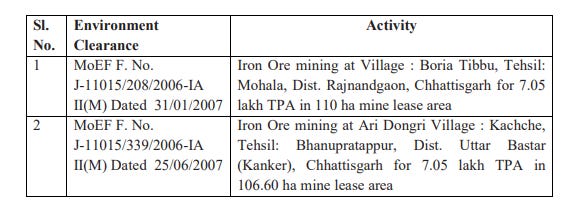

In 2007, the company received environmental clearance to develop its own iron ore mine at Ari Dongri in Chhattisgarh.

Source: Pre-Feasibility Report

This was a turning point. Owning a mine is like a bakery owning a wheat field. It protects you from price swings and ensures that your furnaces never run cold.

Around the same time, the company entered a joint venture to pursue a captive coal block in Chhattisgarh. The logic was simple. If iron ore is the body of a steel plant, coal is its heartbeat. Controlling both meant a steadier rhythm of production and cost.

Source: IIFL Capital

While the physical assets expanded, the corporate structure was being simplified. By 2007, GPIL increased its stake in R. R. Ispat to a full 100%, making it a wholly owned subsidiary.

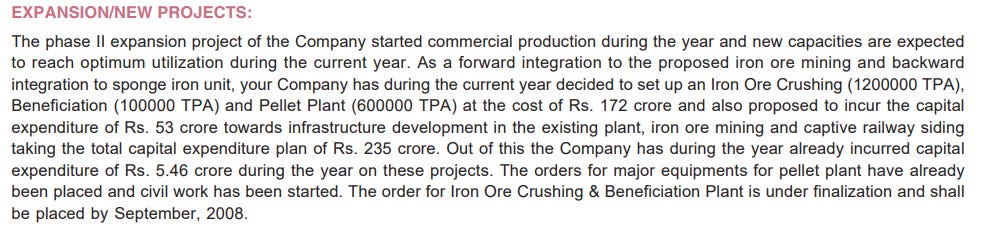

By 2008, GPIL was preparing for a larger leap. The company had launched its Phase II expansion project, adding both forward and backward integration to strengthen the value chain. It planned an Iron Ore Crushing and Beneficiation plant with a capacity of 10 lakh tonnes per annum, and a Pellet Plant of 6 lakh tonnes per annum, together costing about ₹172 crore. Additional investments of ₹53 crore were made in infrastructure upgrades, captive railway sidings, and mining logistics, taking the total capital outlay to around ₹235 crore. Orders for the major equipment had already been placed, and civil work had begun.

Source: 2008 Annual Report

But what about funds?

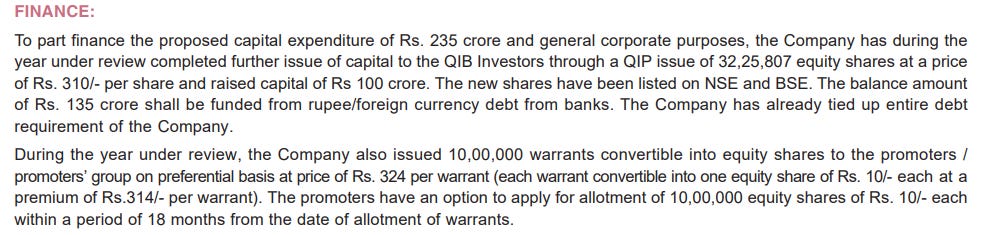

To part-finance this expansion, GPIL raised ₹100 crore through a Qualified Institutional Placement (QIP) at ₹310 each to institutional investors. The balance of ₹135 crore was secured through a mix of rupee and foreign currency loans. Around the same time, the promoters infused more confidence into the business by subscribing to 10 lakh convertible warrants at ₹324 each.

Source: 2008 Annual Report

Then came a larger step. The company merged two group entities, Hira Industries and the remaining operations of R. R. Ispat, into itself. The High Court approved this merger in 2011.

Source: IIFL Capital

This restructuring did more than tidy up paperwork. It gave GPIL direct ownership of Hira Industries’ ferro-alloy plant and its biomass power unit of 8.5 megawatts. It also made Hira Ferro Alloys Limited, earlier a sister company under Hira Industries, a direct subsidiary of GPIL.

Source: Economic Times

By 2011, the transformation was complete. GPIL had turned into a single, unified steel company with mining, power, alloy production, and rolling mills working in sync. What was once a group of related entities was now one integrated organism. Mining fed power, power fed furnaces, and furnaces fed rolling mills. Each part supported the other.

This is what Jim Collins would call a flywheel. Each part of GPIL’s system strengthened the next.

Think of it as a jigsaw puzzle that finally fits together. Every piece, ore, power, alloy, steel, found its place. This unity did not just make operations smoother. It also reduced related-party transactions and improved transparency.

What next?

Now the goal was no longer just integration. It was scale. The company wanted to take every piece of its value chain and make it bigger, sharper, and more efficient.

One major step in that direction was pelletization. In simple words, pelletization is the process of pressing fine iron ore dust into solid pellets that can be used in steel furnaces. You take what would otherwise go to waste and turn it into something valuable.

By 2013, GPIL had commissioned two such plants. The second, commissioned in September 2013, added another twelve lakh tonnes.

Source: Annual Report 2013

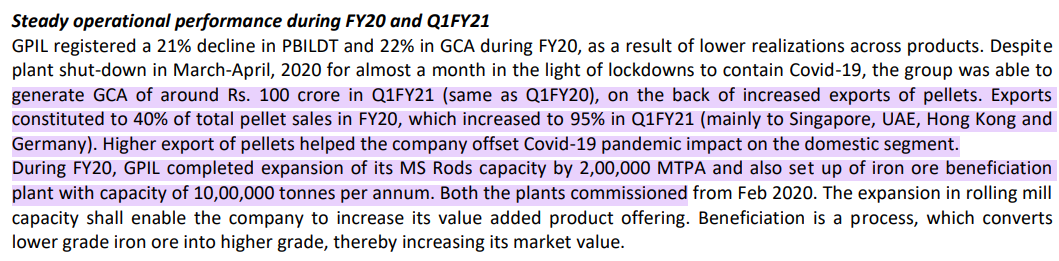

Years later, this decision would prove prescient. When the world went quiet during the lockdowns of 2020, domestic steel demand collapsed, but GPIL’s pellet exports kept its furnaces humming and its cash flows steady.

Source: Care Rating

Alongside the pellet plants, the company expanded its captive power capacity.

Around 2011 and 2012, GPIL also took an unconventional leap into renewable energy. It built a 50MW solar power plant in Rajasthan, operated by a subsidiary named Godawari Green Energy.

For a steel company, this was an unusual venture, but the thinking made sense at the time. The plant had a 25-year power purchase agreement at a high tariff of around 12 Rs per unit. A steady income might act as a cushion whenever the steel cycle turned weak.

Source: MercomIndia

However, there was a trade-off. The solar project cost more than ₹700 crore.

Source: CNBC

At the same time, the company carried its own debt load. Strange right? It showed GPIL’s appetite for innovation but also stretched its balance sheet. Over time, this asset would prove to be non-core and financially heavy, forcing the company to rethink how it allocated capital.

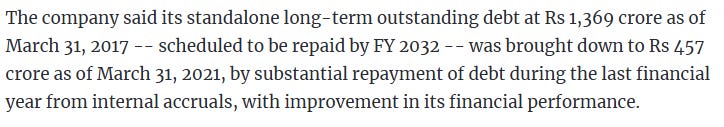

All these expansions, pellet plants, power units, and new capacities were largely funded through debt. By March 2017, long-term borrowings stood at around ₹1369 crore. For a company of GPIL’s size, this was a substantial liability.

The management seemed to recognise the truth.

Every industry, and every company inside it, goes through its own debt cycle. Ray Dalio describes it as the rhythm of borrowing, spending, and deleveraging. First comes easy money and expansion. Then the weight of that debt begins to press down. Eventually, the only path forward is repair.

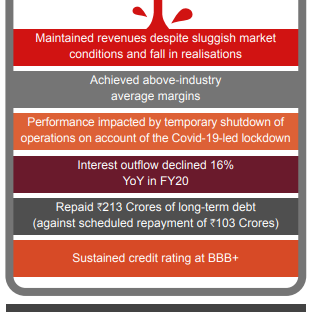

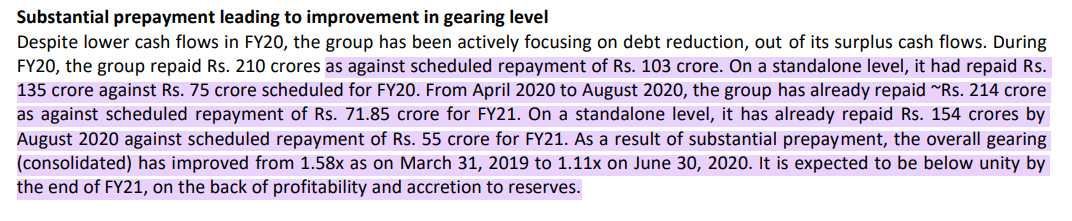

New projects were curtailed, and surplus cash was directed towards loan repayment. The results were visible in the numbers. In the financial year 2020, GPIL was scheduled to repay about 103 cr rupees, but it actually paid more than 210 crore rupees. Even during the first half of 2020, when the world was reeling under the pandemic, GPIL prepaid another ₹213 Cr.

Source: Annual Report FY20

The intent was repeatedly stated by the management. In one of the 2020 earnings calls, Managing Director B. L. Agrawal said clearly that after maintenance spending, every rupee of free cash flow would go toward debt repayment. There was no ambiguity. It was discipline in action.

Source: Q4FY20 Concall transcript

And actually, it wasn’t just about repayment; it was capital allocation discipline. In good times, most managements want to build something new. In tough times, the great ones build balance sheets. GPIL chose the latter. It’s unglamorous work, but it’s what separates a temporary rebound from a lasting turnaround.

Between March 2017 and March 2021, GPIL reduced its long-term borrowings from roughly 1369 crore rupees to about 457 crore. In just 4 years, debt had fallen by 2/3. By mid-2020, leverage had dropped from around half to nearly one time.

Source: Economic Times

Source: Care Ratings

Interestingly, this financial repair took place in the middle of a global crisis. When the pandemic hit, GPIL took the Reserve Bank’s 3-month moratorium to conserve liquidity. But once operations resumed, the company quickly cleared the deferred dues and chose not to extend the moratorium any further. It was a small gesture that spoke volumes about the company’s mindset. Relief was used only as a safety buffer, not as a crutch.

Source: Care Ratings

In July 2021, the company repaid the last ₹457 crore of loans.

Source: Business Line

This was achieved nearly a decade before the original repayment schedule. For a company that once carried heavy leverage, becoming debt-free on a standalone basis was no small feat.

Source: Business Standard

The only remaining borrowing at that stage sat in the solar subsidiary, around ₹340 crore. But that too was resolved soon after, when the subsidiary, Godawari Green Energy, was sold to Virescent. By March 2022, GPIL was sitting on a net cash surplus. After nearly two decades of debt-fuelled growth, it had returned to zero leverage. In the world of cyclical steel businesses, that is a rare and enviable position to hold.

Source: MercomIndia

Once debt was gone, the management’s attention shifted to capital efficiency. It first strengthened the foundation, then began rewarding investors.

The first clear sign came in March 2023. The board approved a share buyback of 50 lakh shares, roughly 4 % of the company’s equity, for ₹500 per share. This represented a premium of nearly 30% over the market price at that time. The total outlay was about two hundred and fifty crore rupees. For a company that only a few years earlier had been focused on loan repayments, this was a statement of confidence.

Source: Company Notification

Dividends followed close behind. Through 2022 and 2023, GPIL paid consistent cash dividends, supported by healthy profits.

With its balance sheet fortified and legacy issues behind it, Godawari Power and Ispat entered a new chapter. This time, the focus was not just on growth, but on growing wisely. The company had learned from its earlier cycle that expansion without prudence can be costly. So, the theme from 2024 onward was simple: grow, but stay financially fit.

The first move in this direction was simplification. GPIL began tidying up what remained of its corporate structure. In March 2024, the board approved the merger of Godawari Energy Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary, back into the parent company.

Source: Financial Express

Simplification often looks boring from the outside, but it compounds quietly. GPIL’s steady mergers and simplifications moved it closer to clarity, one clean structure, one chain of value, no hidden corners.

Godawari Energy had been formed years ago to house power assets. By now, keeping it separate had little operational purpose. Folding it into GPIL made the group more efficient. It removed duplicate filings, board meetings, and compliance costs. It also gave the parent direct access to all cash and assets that had been sitting in that arm.

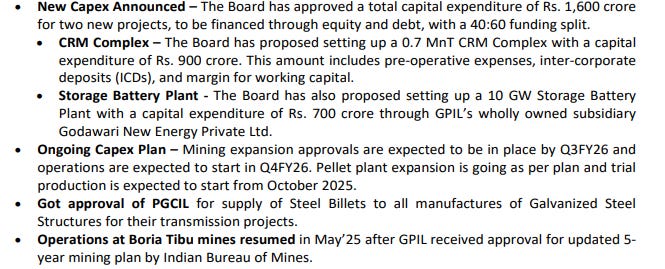

While simplifying, the company was also preparing to build again. In mid-2024, alongside strong earnings, GPIL announced a new capital expenditure program of about ₹1600 crore to be executed over the next few years. But these were not commodity projects. They were value-added ventures designed to make GPIL less dependent on the steel cycle and more linked to consumer-facing and emerging industries.

The first project is a cold-rolling mill complex with a galvanizing and coating line, involving an investment of around nine hundred crore rupees. This facility will have a capacity of seven lakh tonnes a year and will mark GPIL’s entry into flat steel products. Until now, the company mainly made long products such as billets, wire rods, and structurals. Flat steel is a different business. It involves rolling steel into thin sheets or coils, and then coating them for use in automobiles, appliances, and roofing. These products earn better margins and enjoy steadier demand. In other words, GPIL wants to move closer to the end customer. The project is scheduled for completion by 2027 and could redefine GPIL’s position in the industry once operational.

Source: Q1FY26 Result Performance

The second project represents a bold diversification. GPIL plans to set up a battery energy storage system factory with a total capacity of ten gigawatt-hours. The investment here is around seven hundred crore rupees. This venture will be housed under a new subsidiary called Godawari New Energy Private Limited. It is trying to move from just producing green power to also building the tools that store it. The project is expected to be ready around 2026 or 2027. It is a risky but forward-looking bet that could open a second growth engine beyond steel.

Source: Q1FY26 Result Performance

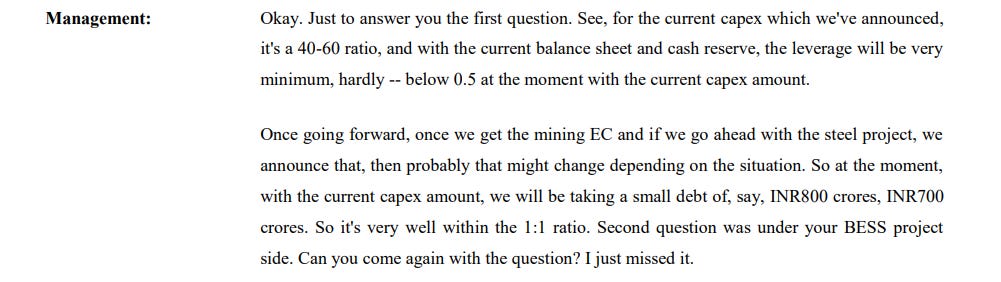

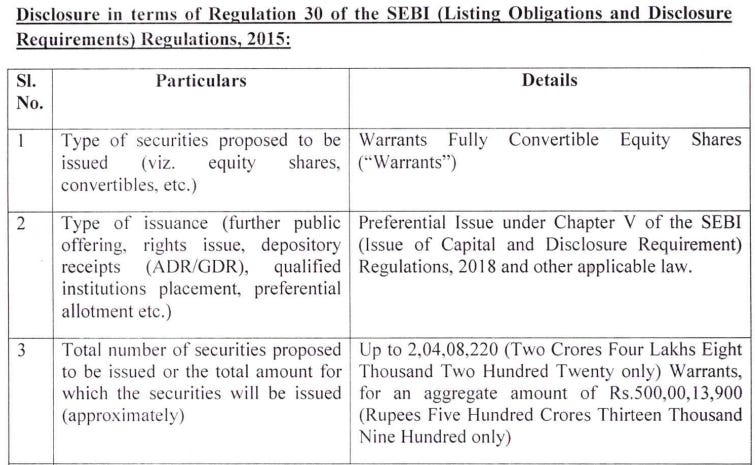

Funding these projects is where the company’s prudence shows. GPIL has guided for a balanced mix of about 60% debt and 40% equity for the total sixteen hundred crore plan. With no existing borrowings on the books, even taking on 960 crore of new loans keeps leverage modest. On the equity side, the board approved an issue of convertible warrants in September 2025 to raise up to ₹500 crore. Roughly two crore warrants priced at ₹245 each will be issued to promoters and a few investors.

Source: Q1FY26 concall

Source: Company Notification

When promoters invest their own money alongside public shareholders, it shows what Nassim Taleb calls skin in the game. It means they don’t just share the upside; they share the risk too. For GPIL, the warrant issue wasn’t just fundraising; it was a message. The people running the company are betting their own capital on the same future they are promising others.

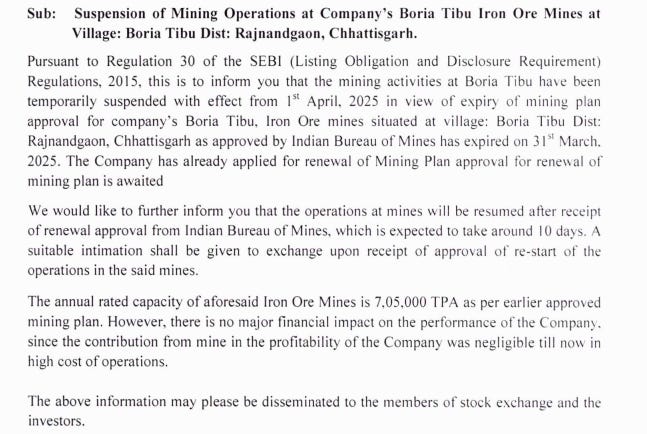

Operationally, 2025 brought a small but telling reminder of how much GPIL’s success still depends on regulatory coordination. The Boria Tibu iron ore mine, which had been producing steadily, had to pause operations when its mining plan expired at the end of March 2025.

For about two months, no ore could be extracted. The company moved quickly, and by late May, it secured a new five-year plan from the Indian Bureau of Mines.

Mining resumed on May 27, 2025, and supply was restored.

Source: Q1FY26 Result Performance

During the next investor call, the management confirmed that the expansion of the larger Ari Dongri mine from 2.35 million tonnes to 6 million tonnes per year was expected by the first quarter of 2026.

Source: Q1FY26 Result Performance

The story of Godawari Power and Ispat is, at its core, a story of transformation. It began as a small regional sponge iron maker in central India and evolved into a fully integrated steel enterprise. It went through the familiar cycle of growth and debt, of expansion and restraint, and emerged stronger each time. From being a leveraged micro-cap struggling under loans to becoming a debt-free, cash-generating company, GPIL has travelled a long way.

Today, it stands at another turning point, shifting from being a pure commodity producer to a more technology-driven, value-added business.

What GPIL is playing now is what Simon Sinek calls the infinite game. It’s not chasing the next quarter or even the next cycle. It’s building systems that can adapt, survive, and stay relevant decade after decade. Debt-free growth, cautious diversification, and long-term capital stewardship are the rules of that game.

Each phase of this journey has carried a lesson in adaptation. The company learned to integrate when margins were thin, to consolidate when leverage grew heavy, and to diversify when the cycle began to mature. It shows how patience and capital discipline, when practised over years, can quietly build enduring value.

In many ways, GPIL’s story mirrors the broader truth about industries built on iron. Iron has not only created wealth for Tony Stark from Iron Man, but also for those real-world entrepreneurs and investors who understood its cycles. When the steel cycle turns up, it rewards those who built wisely during the down years. GPIL’s promoters and long-term shareholders know that rhythm well.

As of the mid-2020s, the company stands as a reminder that enduring businesses are not defined by their setbacks but by how they respond to them. Strong foundations, careful balance sheet management, and a clear sense of direction have turned every challenge into an opening for renewal. The journey of Godawari Power and Ispat is not just about steel and power; it is about foresight, discipline, and the compounding power of persistence.

Do you know that, as recently as June 2022, GPIL was a micro-cap stock? Hidden. Undiscovered.

And I am not done yet. I will cover two more similar stories from the same sector. My job is to make you understand one often-ignored fact. Commodity businesses do not just receive large volumes of products they serve. They can also make generational wealth for their promoters and shareholders if done right.

Is it easy? No.

Possible? Definitely!

Are you ready?

Reply in the comments with a “Yes” :)

It gives me motivation and helps the Substack algorithm to recommend this post to other Substack readers as well.

Disclaimer: Zen Nivesh - No Holding, Harshal/Writer - No Holding. No Recommendation to Buy/Sell.

And if you’ve found value in our research and investment playbook, and are keen on subscribing to our upcoming Micro-cap (₹3,000 Cr market cap and below) Stock Advisory, know this.

~900 smart investors have joined the waitlist of our micro-cap-focused stock advisory.

~600 of them wish to have early access to ZN Playbook.

Early access begins this weekend. This is your last opportunity to join. Before the rest.

Wow! This was some Read - Harshal ... U have got a flair for writing for sure - do keep them coming - as Yeh Dil Maange More :)

Have been holding GPIL since early 2022 ... Have Booked some profits in between - but still have it in PF ... And it has been a rewarding Journey so far - for sure.

What I wanted to particularly highlight is that I had looked at GPIL and invested for right reasons and saw the same Synergies that U have so well articulated in your Blog above - but mine was a more of a Numbers Story and understanding the Levers Mgmt was applying - so my thesis bottom line again was betting Big on Management and how they are Walking-the-Talk ...

But reading your article, where U R stringing the whole sequence with such a flair - became bit more proud of the GPIL Mgmt - and that warm feeling: that my thesis was right to bet Big on GPIL ... U have successfully brought GPIL in my Focus once again - Excellent writeup tends to do that .... So, Take a Bow

Looking to Read More and More

Great going harsh , looking forward for more